programme management

Seven questions to build a roadmap

In my last post I wrote about why roadmaps are for everyone. This post is about techniques for building one and how the use of language can help align your pure agile or mixed methodology programmes.

In government service delivery programmes there's always a mix of methodologies between agile and waterfall. Some of this is cultural, some of this is for practical reasons. The techniques I describe below fit within this context.

The prerequisites

The prerequisites for a good roadmap are good leaders and clearly articulated goals. If your future is driven from above by preconceived thinking or your teams don't emotionally buy-into the programme's goals it's not a happy place.

Good leaders set and articulate goals that inspire you. They allow teams to challenge the seemingly sacred. They empower them to come up with creative approaches to achieving strategic goals. If you don't have these then your roadmap could end up as an exercise in group-think.

Ask 7 simple questions

Gather the team and your subject experts (e.g. ops, legal, security, policy, HR) and ask yourselves these questions*:

What are we trying to learn or prove?

Who are the users?

What are we operating?

What are we saying?

What are our assumptions?

What are our dependencies?

What capabilities do we need?

A timeline is not dirty

The Waterfall methodologists feel comfortable with long timelines. They typically work 'right-to-left' from a desired delivery date; the agilists prefer to work iteratively, 'left-to-right' as much as, and where possible. Whatever your preference, timelines are important and an inescapable part of delivering. A timeline is not a dirty concept.

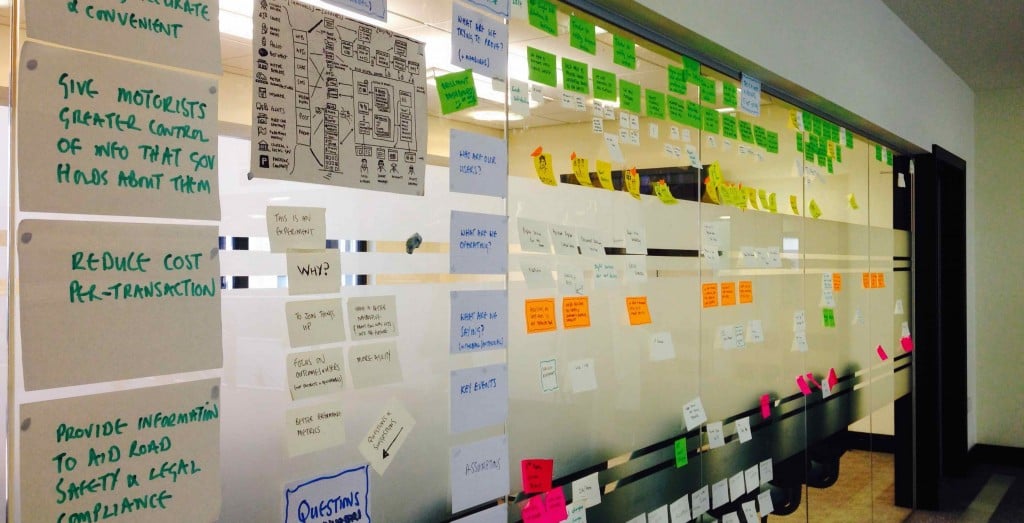

I start this conversation by sticking post-its across the top of a wall with time intervals running left to right. I use 3 or 6 monthly intervals over 1 or 2 years, but whatever is right for you. Choose a timeframe that creates some discomfort for your colleagues to think beyond the immediate "deadline" in everyone's head and to get them to think strategically.

Place known, real or imagined, time constraints and events across the top too, maybe on a smaller or more muted colour post-it so they don't become the only focus of conversation.

You get better roadmaps by asking questions

The language you use is important. Asking everyone to answer questions is good for finding common ground and helps get better inputs. Asking "What are we trying to prove or learn?" for each time interval helps people think about the evolution of your service and grounds it in iterative delivery.

The agilists are used to thinking about learning and value-based incremental delivery. They feels comfortable with it. The waterfall methodologists typically think more about deliverables. That's OK, you can easily ask what are the outcomes they want from it? What will it prove when we deliver it? What will we learn from delivering it?

Ask how we measure stuff and set some sensible targets. These be your performance indicators (KPIs) and a step towards an awesome dashboard for your programme.

Who are the users? Everyone wants to deliver for users so no controversy. No one is itching yet.

"What are we operating?" gets people thinking about the service as a whole and how it will work and evolve over time. Talking about it with everyone helps. It gives teams focussed on digital a feel for challenges of the Operations folks (e.g. in the job centre, in warehouses, on the service desk) and Operations get to say how they want to rollout and operate it.

Capture assumptions and dependencies whenever they come up in conversation. That always helps bonding.

A roadmap can write your comms plan for you. By asking "what are we saying?" (to your organisation, your users, the press) for each time interval you are telling the story of your evolving service. The Comms folks are now itching but I think it is excitement not concern.

Capabilities are to do lists for everyone

Finally, "What capabilities do we need?" (to operate the service). I find everyone gets the word capability after a gentle nudge (e.g. pay, inbound-telephony, search, dispatch, training). Add a description and an owner to each one if you can. Describing them and giving them a label is hard but both the agile and waterfall camps understand the word and can come up with a sensible list of them.

The agilists, especially the architects, can begin to see the beginnings of their systems, the epics and minimum-viable features within their backlogs. The waterfall folks can imagine their gantt charts and what needs doing by when.

Show it off. Get people talking about it

These techniques give you a holistic view of the service from a near standing start. This exercise does not answer everyones' questions. There's still uncertainty and no one feels 100% comfortable with the unknowns, but you have the backbone of a strategic approach. One that is grounded in user centred, iterative delivery and provable outcomes.

Everyone can take something away with them and use it to inform their own planning activities - whatever they are. Turn it into an illustration if you like. Present it to important people. Keep pointing at it, talking about it and improving it.

This is your roadmap.

* I want to credit Richard Pope who came up with some of these questions on the hoof when I did this for the first time. I've run with them and tweaked.

Everyone loves a roadmap

In agile programmes people prefer to talk about roadmaps rather than plans. This post is about the reasons behind this and the benefits of using a roadmap rather than a gantt chart to manage pure agile, or mixed methodology programmes.

Peoples' Front of Judea

Plans can be a cultural battleground between the traditionalist and agilistas. They needn’t be. Both camps need an artefact to guide them towards a longed for future and a roadmap provides something for everyone to cling to.

Managers and stakeholders often ask when something will be ‘done’; What are the milestones? Are we on track? What are the dependencies? What is the critical path? These are natural questions to want to ask. Waterfall and agile methodologies answer them in different ways with very different artefacts.

The Waterfall-istas reach for MS Project or equivalent gantt tool to make sense of the world. The agilistas use a backlog, prioritisation, continuous delivery and feedback loops to make sense of theirs.

Agilistas will say “we love planning… just not plans”. They hate gantt charts because they offer only false certainty and often do not sufficiently accommodate change. In the wrong hands they will stifle learning and continuous improvement, as teams switch the focus from delivering outcomes to keeping to ‘the plan’.

Continuous, adaptive planning is an awesome part of agile. Good, informed prioritisation, that factors in the cost of delay, risk, business value and dependencies is perfect for wholly agile teams, but it’s not for everyone.

Not everything is software or agile

My particular experience is in the delivery of digital public services for government. Mostly these programmes of work are not just about digital. They may include a change to an organisation’s operating model, training, buildings, telephony… Often the (least lean) bits of service delivery that many agile teams sometimes consider as “the business-y bit” – bywords for “waterfall” and “dealing with the non-converted”.

Traditionalists charged with managing these types of programmes see no alternative but to add agile sprints to the large MS project plan. In the past, for example, I’ve been asked to provide themes by way of labels for six months of two week sprints and this is not good — for anyone.

They get frustrated with agile's lack of plan and I understand their concerns. I’ve seen agile planning ceremonies used as a smoke screen for short-term planning only. That’s being über agile, right? Yes it is, but sticking with that mindset can alienate stakeholders and co-deliverers who demand a better picture of the future.

A roadmap is the droid you are looking for...

A roadmap bridges the gap between worlds.

Something for everyone - it is an artefact that traditionalists recognise enough as a 'plan' and agilists recognise as 'not a gantt chart'.

Focuses on outcomes not deliverables -it promotes the right sort of strategic conversations within teams and with stakeholders.

Provides stability but evolves - it sets a clear, stable sense of direction but I find teams and stakeholders feel more comfortable discussing change resulting from iterative delivery and learning.

Promotes buy-in -good people will feel out of control and disengaged when deliverables are dictated up-front and/or from above. Self organising, multi-disciplinary teams love to own and be empowered to meet outcomes in creative ways.

More coherent - it allows you to knit all aspects of your programme together (e.g. software, infrastructure, ops, policy, security, estates, human resources, procurement) without freaking out any horses or doing up front requirements specs or giving false certainty.

Better performance metrics -outcome based planning allows programmes to more easily measure the evolution of a service through early stage delivery into full blown operation and iteration. Some metrics will be a constant throughout, others will only have relevance in later stages. This approach keeps you iterative and chasing incremental improvement. It also makes for joyful dashboards.

Better governance -roadmaps work well with time-boxed or target-based governance gates -- you choose.

There's something for everyone to like about a roadmap.

In my next post I'll talk how to put one together and how language can be used to find common ground.

What I've learnt about scaling agile to programmes

This was first published on the Cabinet Office website. Well, we did it! We delivered GOV.UK. It was big and hairy and we did it by being agile. The benefits are clear:

- We were more productive: By focussing on delivering small chunks of working product in short time-boxes (typically 1 week development sprints) we always had visible deadlines and a view of actual progress. This is powerful stuff to motivate a team.

- We created a better quality product: We used test driven development; browser and accessibility testing were baked into each sprint and we had dozens of ways of testing with real people as we went along to inform the design and functionality of the product.

- We were faster: By continually delivering we were able to show real users and our stakeholders working code very early on and get their feedback. What you see now on GOV.UK was there in February, albeit in a less fully featured and polished way. Lifting the lid on it did not seem like a big reveal; it felt like an orderly transition.

These characteristics are true of all our projects, but I wanted to talk about agile at scale with 140 people and 14 teams and what I've learnt. In so far as I know this is a relatively new area and there is not a consensus view of how to do it.

Be agile with agile

The foundation of this success was people that were agile with agile. Props to people like Richard Pope who helped set the tone of our culture at GDS, which is one where people are open to learning, improving and workspace hacks without the dogma of big 'A' agile. It’s all about that. If you don’t have this embedded in your teams then what I write below doesn’t matter.

Lesson: a working culture that values its people and embraces experimentation is essential to success.

Growing fast is hard

We grew from a cross-functional team of 12 for the Alpha version of GOV.UK, to a programme of work involving 140 people over 14 teams. There was a period from April to June where we grew 300% in three months, which was crazy but felt necessary due to the scope of work.

Our expansion was organic and less controlled than our original plans had suggested. Had we focussed on fewer things from the outset, the overhead of getting people up to speed and the additional communication needed to manage this would have been far less and our momentum would have increased.

Lesson: We should have committed to doing less like the books, blog posts and experts say.

Don’t mess with agile team structures

Clearly defined roles within teams as Meri has said are vitally important. Our teams emerged rather than beginning the project formed with the core roles in place. The consequence of this compromise was a blurring of roles which meant that certain people took on too much. In these teams people faced huge obstacles around communication, skills gaps, confused prioritisation and decision making and ultimately productivity suffered.

Lesson: This experience reinforced the importance of agile team structures. Don’t mess. The team is the unit of delivery!

Stand-ups work for programmes

When you have a team of 10 people conversations can happen across a desk or during stand ups. As we expanded rapidly communication became increasingly strained. There were fewer opportunities for ad-hoc conversation and talking between teams was harder. We solved this with a programme level ‘stand-up of stand-ups’ attended by delivery managers from each team.

We had up to 14 people and we nearly always managed to run it within 15 mins. We held ours twice a week which gave us good visibility and opportunities to help each other. People willingly came along, which I take as a good sign the meeting was valuable.

Lesson: In the future we’ll probably split this into another level of stand-ups so we have one for teams, one for working groups of teams (or sub-programmes) and one for cross-GDS programmes.

Monitor with verifiable data

We organised the programme into working groups which had one or more teams. Most teams used a scrum methodology and split their work into releases (or milestones), epics and user stories.

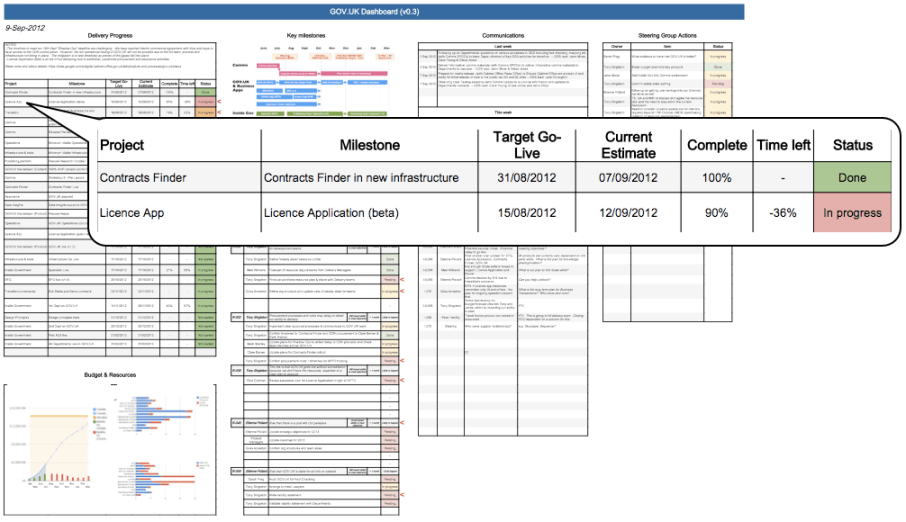

By tracking these we generated verifiable data about progress, scope completeness and forecasts of delivery dates. By aggregating this data we created a programme dashboard for teams and senior management.

The image above shows the GOV.UK programme dashboard. This view of the programme was created using data generated by the teams doing their day-to-day work using tools like Pivotal Tracker and was not based on subjective reporting by a project or programme manager. The callout shows two milestones for two different teams. One was completed, the other is shown to be 90% complete with an estimated delivery date a month later than our target date. This was verifiable data based on the number of stories and points left to deliver the milestone with historical data on a team’s speed to build, test and deploy the remaining scope.

This was the bit that made me most happy and made tracking and managing the programme much, much easier than gantts.

Lesson: Use independently verifiable data from your agile teams to track your programme

Use Kanban to manage your portfolio

We used a system of coloured index cards to map out the components of the programme. This captured key milestones, major release points and feature epics and because it was visible, it encouraged shared ownership of the plan and adaptive planning throughout the delivery.

We gathered Product Managers, Delivery Managers, the Head of Design and the Head of User Testing around this wall every two weeks to manage our portfolio of projects and products. The process forced us to flag dependencies, show blockers and compromises.

Lesson: This approach was successful up to a point but in hindsight I wish we had adopted a Kanban system across the programme from the outset. It would have provided additional mechanisms for tracking dependencies, limited work in progress and increase focus on throughput. I would also formalise a Portfolio Management team to help manage this.

Everything you’ve learnt as a project or programme manager is still useful

When I started using agile, someone said me, “when things get tough and you want to go back to old ways, go more agile, not less”. This has stuck in my mind.

When I was designing the shape of the programme and working out how we would run things I wanted to embed agile culture and techniques at its heart. For example, we used a plain English week note format to share what happened, what was blocking us sprint to sprint rather than a traditional Word or Excel status report.

In tech we always say we’ll use the right tool for the job and in programme management the same is true. In the same vein I opted to use a gantt chart as a way of translating milestones and timings to stakeholders but internally we never referred to it and were not slaves to it.

Risk and issue management is an important aspect of any programme. The usual agile approach of managing risks on walls scaled less well into the programme. Typically in smaller teams you might write risks, issues and blockers on a wall and have collective responsibility for managing them. We scaled this approach to our stand up of stand ups and this worked well for the participants: it was visible, part of our day to day process, we could point at them and plan around mitigation.

But there was a moment when the management team asked for a list of risks and issues and pointing them at a wall was not the best answer so we set up a weekly risks and issues meeting (aka the RAIDs shelter) and recorded them digitally. This forum discussed which risks, issues, assumptions and dependencies were escalated. By the book it fits least well with the agile meeting rhythm but it gave us a focal point to discuss concerns, plan mitigation and fostered a blitz spirit.

We have some way to go to make it perfect but we have learned that within GDS agile can work at scale. We’ve embraced it culturally and organisationally and we’ve learnt an awful lot on the journey. Some of the lessons we've learnt have already been incorporated into how we’re working now and I look forward to sharing more about this in the future.